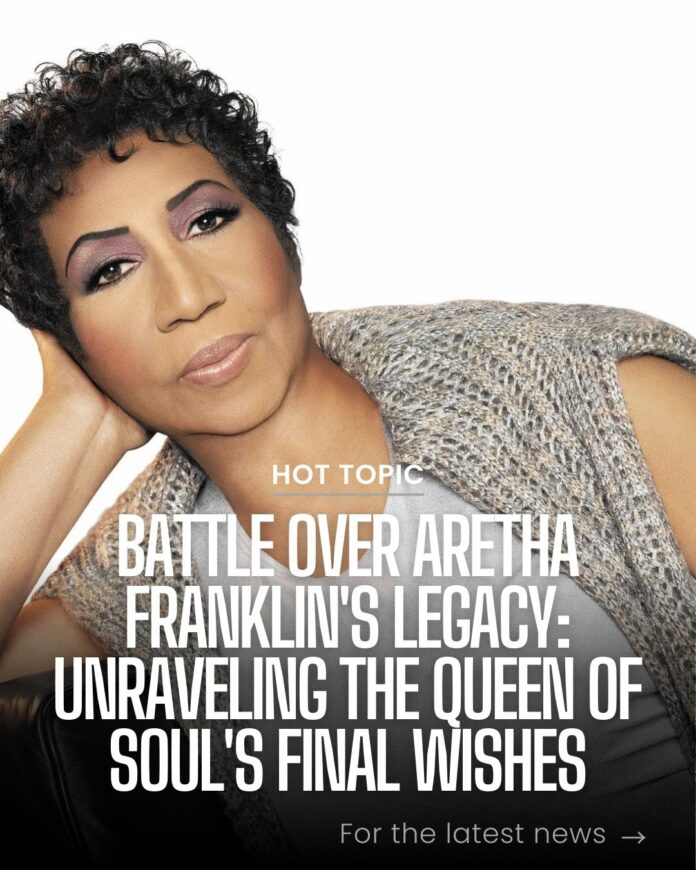

Five years after her passing, the final wishes of music legend Aretha Franklin remain unresolved, as an extraordinary trial commences to determine which of two handwritten wills, including one discovered in couch cushions, will govern the handling of her estate. Despite years of health issues and attempts to formalize her will, the Queen of Soul, who had four sons, did not leave behind a formal, typewritten document. Nevertheless, Michigan law allows for the consideration of other documents, even those with scribbles, scratch-outs, and hard-to-decipher sections, as her intended directives.

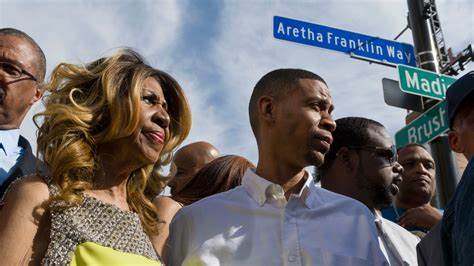

The dispute revolves around one son pitted against the other two. Ted White II contends that the papers dated 2010 should primarily dictate the estate’s distribution, while Kecalf Franklin and Edward Franklin favor a 2014 document. Both wills were found in Franklin’s suburban Detroit home several months after her demise at the age of 76 from pancreatic cancer.

While there are similarities between the two wills, suggesting that the sons would share music-related income and copyrights, differences emerge upon closer examination. The older will designates White and Owens as co-executors and stipulates that Kecalf and Edward Franklin must pursue business education and acquire a certificate or degree to benefit from the estate. Conversely, the 2014 version removes White as executor and appoints Kecalf Franklin in his place, omitting any mention of business classes.

In terms of assets, Kecalf Franklin and Franklin’s grandchildren would inherit her primary residence in Bloomfield Hills, initially valued at $1.1 million but significantly appreciated since her passing. The property, often regarded as the crown jewel, holds substantial value, according to Craig Smith, Edward Franklin’s attorney.

Notably, the eldest son, Clarence, is diagnosed with a mental illness and resides with support in a group home outside of Detroit. In one of her wills, Aretha Franklin instructed her other sons to oversee Clarence’s well-being and check in on him weekly. However, the 2014 will does not list Clarence as a beneficiary.

Furthermore, in her 2014 will, Franklin stated that her gowns could be auctioned off or donated to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, emphasizing the need for consistent support for her eldest son, Clarence, who lives under guardianship.

Charles McKelvie, an attorney representing Kecalf Franklin, argued in favor of the 2014 document, stating, “Two inconsistent wills cannot both be admitted to probate. In such cases, the most recent will revokes the previous will.” Conversely, White’s attorney, Kurt Olson, highlighted that the 2010 will was notarized and signed, while the later version appeared to be merely a draft, lacking the necessary attention one would expect from a legally binding will.

As the trial unfolds, the fate of Aretha Franklin’s estate hangs in the balance, with the court tasked with determining which will should govern her final wishes. The Queen of Soul’s enduring legacy and the family’s unity are at stake as her sons contend for their respective interpretations of her intentions, all while grappling with the absence of a formal, undisputed will.

Follow “Aretha Franklin”

Written by:

Dana Sterling-Editor